"Bestial Cruelty": Was Islam Truly Spread by the Sword?

Exploring a loaded millennial statement, intimately linked to politics, theology, and the "Islamic / Western" World divide

“Who are Muslims and Why Do They Want to Kill Us?”

If you’re ever lucky to be in Paris -and have limited command of french- I invite you to go to any branch of a store called “fnac”.

Fnac is a general multimedia store popular in France. It was always a pleasure of mine to browse their book selections in hopes of finding a new read.

The best sellers where displayed on giant white tables upfront, making it easy to see what the french public was into at the time.

Slowly, an entire selection of books started to pop-up on these displays. Books like:

“Who are Muslims and Why Do They Want to Kill Us?”

“Islam and the Fall of Western Civilization”

“Mohamet, is he the devil?… Or is he worse?”

I exaggerate perhaps, but also, not at all.

Needless to say, it becomes pretty traumatic for a muslim to wander around certain sections of the store, seeing what people are reading these days.

An interesting motif emerges on the cover design though, intimately associated with the idea being pushed in these books.

Can you guess what it is?

An Islamic-style sword.

A straightforward recall to an oft-repeated “truth” relating to Islam: “Spread by the Sword”.

Discussing the relationship between Europe and the Islamic world will take many issues of this newsletter, but it is fitting to start at the very beginning:

Where did “Spread by the Sword” come from?

Now first it is important to define terms properly: Is “Spread by the Sword” talking about Islam as an Empire and a political entity?

If so, then yes, absolutely, it did spread by the sword, via armies, like any other empire building exercise would have.

If we are discussing spread as a religion, coerced through conversions under threat, then “Spread by the Sword” is an entirely different story.

It begins in the 12th century, where Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny in France, initiated a major translation project aimed at bringing Islamic literature, including the Quran, into the Latin world.

The opus compiled is what is known today as the “Corpus Cluniacense”.

Peter the Venerable is celebrated today as a Saint, often hailed for his endeavors to build a better understanding of Islam in Europe.

What certain sources fail to mention is that his only desire to understand Islam was to better refute it, showcasing its heretical nature compared to Christianity.

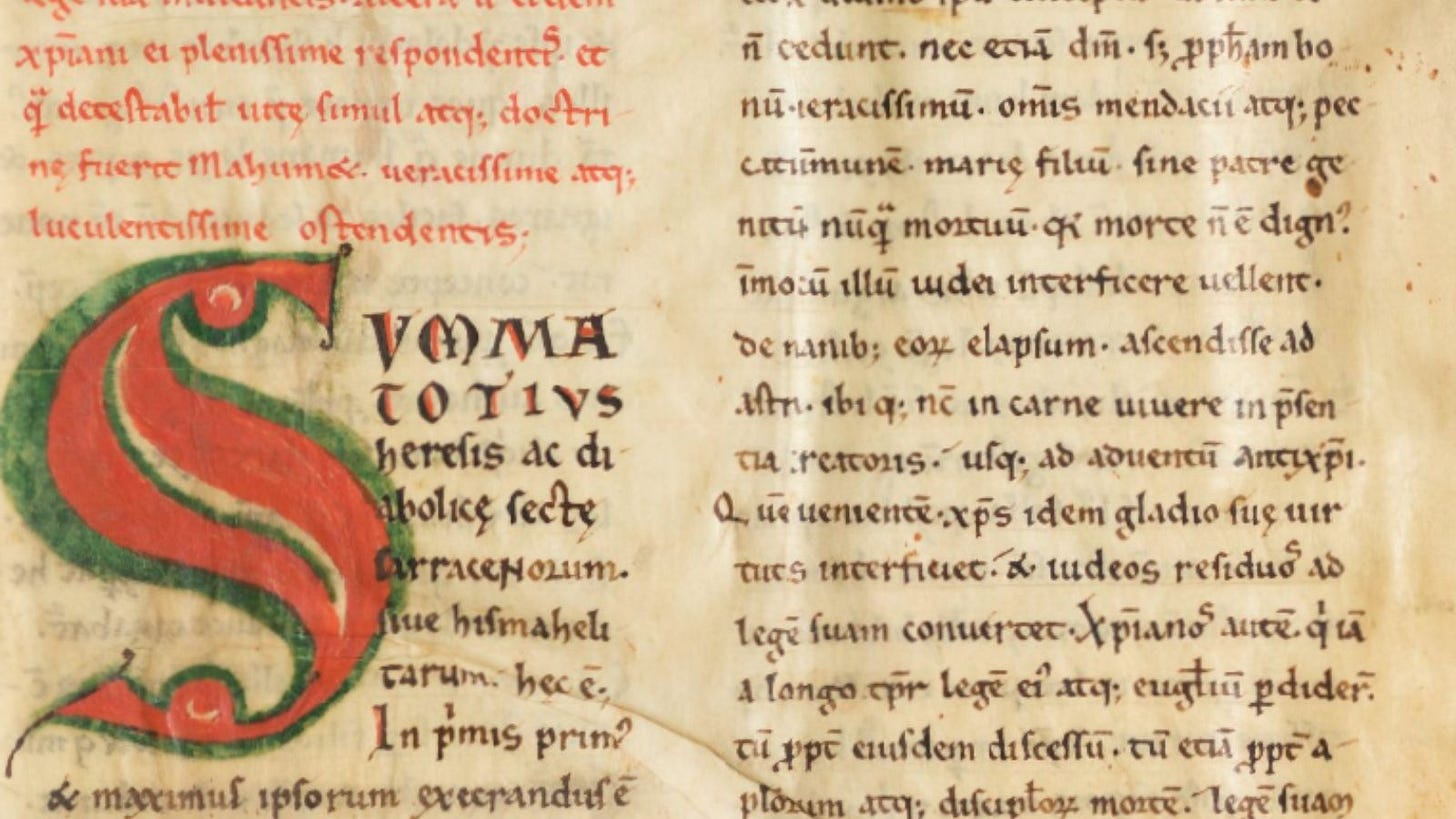

This can easily be seen in his treatise, aptly titled: Summary of the Whole Heresy of the Diabolical Sect of the Saracens.

In it, Peter the Venerable contemplates the “bestial cruelty” of Islam, claiming there it had “spread by the Sword”.

As Karen Armstrong, famed religious historian, puts it: “Peter was writing at the time of the Crusades. Even when Christians were trying to be fair, their entrenched loathing of Islam made it impossible for them to approach it objectively.”

These fearful retellings endured for centuries as collective tradition, until it was picked up in the late 19th and 20th century by Orientalists, who codified them as part of their academic treatises on “the Orient”, and finally surfacing today in Western media outlets.

Regardless of the context of the claim, the question still begs itself: did Islam -in fact- spread by the Sword?

The answer that most modern historians give is no. And that for many reasons, some quite noble, others more on the…err… practical side.

1. Theological Implications

The most straightforward reason. The Quran is clear in many verses that forcing people onto religion is forbidden.

An often repeated verse that all muslims know is:

"لا إكراه فى الدين قد تبين الرشد من الغى"

“Let there be no compulsion in Religion; Truth stands out clear from error.” [2:256]

2. Pre-Existing Guidance

Unlike many other religions, Islamic law already has provisions as to how to deal with non-muslims in an islamic society.

Since guidance already exists, the “conquerors” didn’t need to do much to know how to deal with their new subjects.

The famous French polymath Gustave Le Bon stated in his book, Arab Civilization, “Power was not a factor in the spread of Islam; that’s because Arabs left the people they vanquished free to practice their own religion.”

3. Law of Numbers

Another explanation put forward to debunk this claim is simply the small number of muslims in their conquered lands, perhaps about 10% of the total population in Egypt and 20% in Iraq in their early days.

As such, even if they wanted to force others to convert, it would have been impossible, as they would have been overwhelmed by the local populations.

4. Taxation and Treasury Advantages

Non-muslim living in muslim lands are required by Islamic Law to pay a specific form of tax.

Muslims also have their own “tax” to pay in the form of compulsory charity, supplemented by additional voluntary charity that many participate in.

This Muslim “tax” is beneficial to the state, by providing those that are underprivileged welfare, building roads, hospitals, mosques, schools, bridges, etc.

But this income is highly regulated by Islamic law, usually staying local, and strictly regimented in its application.

Non-muslim taxes on the other hand go straight to the central authority, into the muslim ruler’s treasury, and can be disposed of as the ruler pleased.

As such, you could put forward that financially, it made more sense to muslim rulers to not convert others to Islam, for their personal treasury gains.

Beyond all of this, a quick overview of Islamic history can also easily debunk the “spread by the Sword” myth:

Indonesia was until very recently the biggest Islamic country in the world, yet no Arab or Islamic armies arrived at their shores, and Islam spread there with the arrival of muslim merchants. The same applying to Malaysia.

Islamic expansion never set foot in Western Africa, yet many of these societies are muslim today.

India, even after 800 years of muslim rule, is still a majority Hindu country, with muslims making up only 20% of the population. With almost a millennium of Islamic rule, this would have been a ripe ground for forced conversions, and Hinduism would have been rendered a tiny minority there.

Dr. Wael Hallaq, Professor in Humanities at Columbia University, states that muslims were a minority in the “Levant” region well into the 4th century after Hijra (~10th century CE).

It is important though not to fall into another trap:

While “spread by the sword” is one end of the interpretation spectrum, painting a picture of Islamic utopia where all was fine and well is another extreme.

There have been, of course, cases of forced conversions in Islamic history.

No society is perfect, and rulers and adherents will misbehave, across religions and ethnicities.

Yet, as most historians seem to assert, these incidents are rare and far between.

Even noted Orientalist De Lacy O'Leary wrote: "History makes it clear however, that the legend of fanatical Muslims sweeping through the world and forcing Islam at the point of the sword upon conquered races is one of the most fantastically absurd myths that historians have ever repeated."

Beyond violence, Hassam Munir, Yaqeen Research Fellow, attributes the spread of Islam to a mix of -but not limited to- da‘wah, trade, intermarriage, social influencers and migration.

What is remarkable though, is the endurance of the violent “spread by the sword” myth.

In this humble opinion, it is clearly due to the bloody and evocative nature of its phrasing.

If it was simply “Islam was forced on others”, I’m not sure how much that trope would have endured.

But just like the “40 decapitated babies” story that played out recently in western media, a visual image of people on their knees, sword to their necks, forced to convert or die?

That’s hard to shake.

Be well,

Majd

The Green Pill will be back next Thursday. In the meantime, check out the rest of our “amazing” content here.

Did you enjoy this issue of The Green Pill? Help us spread the word then. Think of one specific person around you that might enjoy this content, and share with them.

Love to hear your thoughts + constructive criticism welcome

Sources